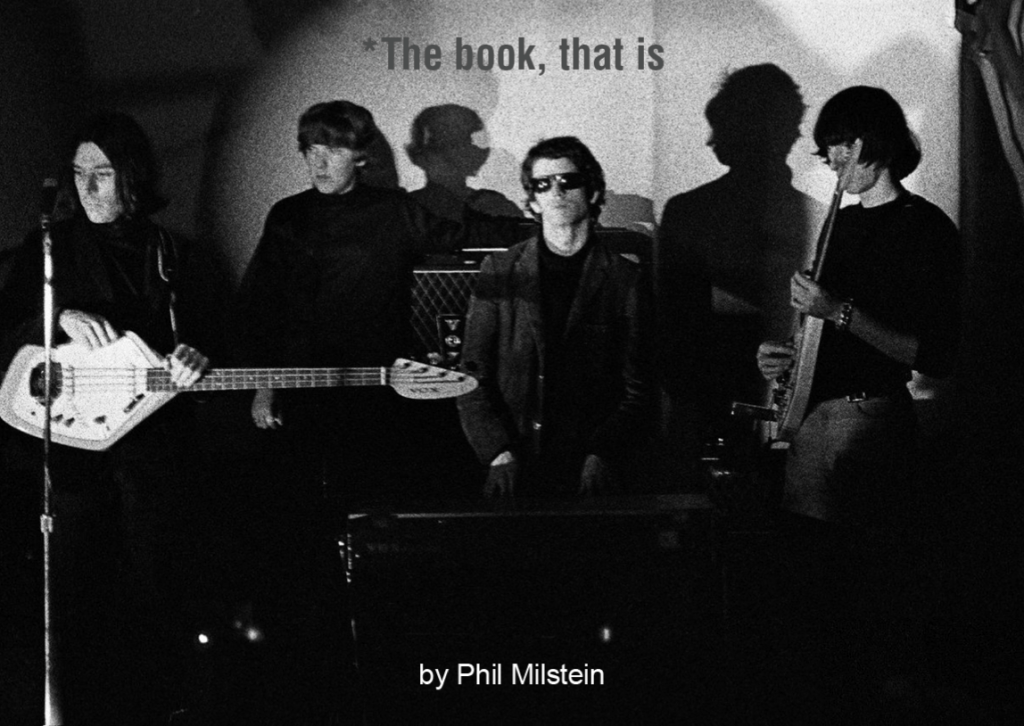

Hisham Mayet and Bulbous Monocle Records – a Q&A

I’m a strong enthusiast and supporter of Hisham Mayet and his Bulbous Monocle label’s efforts to excavate, illuminate and re-introduce to the world the odd and offbeat San Francisco musical underground of the late 1980s and 1990s. Starting with a quartet of out-of-print or otherwise uncollected Thinking Fellers Union Local 282 records, Bulbous Monocle has some big plans and a set of aesthetic interests that are pretty goddamn compelling.

I took the time to talk with label proprietor Mayet – who already runs Sublime Frequencies and a couple of other spin-off imprints – about the label, his “journey” and a few other items of interest during the summer of 2024:

Dynamite Hemorrhage: Let’s start with an Executive Summary question and have you give us the overview of Bulbous Monocle – what it is, why you started it, and what you’re trying to capture with this label.

Hisham Mayet: I guess several years ago, sometime pre-pandemic here in Portland, Mark Davies (Thinking Fellers Union Local 282) had become a close friend. Over the years I’d certainly met Mark, probably during the tail end of my time in San Francisco, and I definitely got to know him a little bit better post-that. Once I moved to Portland in 2009, I got to really know all those guys, really. It was a matter of all of us sort of moving to Portland around the same time, give or take a few years. I think Mark and Kate, his wife, moved up here a little earlier than Brandan (Kearney; World of Pooh and Nuf Sed records), who moved in about a year before I did.

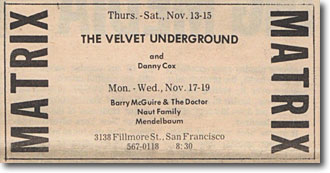

We all had common friends, obviously, from the centrifuge of Sun City Girls and Mark Gergis. That whole sort of post-SF scene. We found a bunch of us ended up in Portland, either from San Francisco or down from Seattle, whatever, and got to be close, I don’t know; drinking buddies, dinner parties, hangout sessions, etc. We were one day just shooting the shit, I think, at a bar or something, and I was like, “Hey, man – what’s going on? The Thinking Fellers archive….?” I think I’d done some snooping around the Internet and discovered that everything was out of print for sure. There’d been no activity. The last time there was anything of significance from that band was a reunion show back in 2010 or 2011 or 2012. There was this festival in the UK called All Tomorrow’s Parties. That one was curated by Animal Collective, and they had invited Thinking Fellers to play. It was a host of real famous names, it was wonderful; Rick and Alan Bishop as the Brothers Unconnected duo; Sublime Frequencies DJ’s, and host of others: Terry Riley, The Frogs, Meat Puppets. Fuck. It was insane.

Beyond that, there had just been crickets. I was just telling Mark that “it’s a real shame that no one’s really talking too much about the Fellers anymore, and what are you planning on doing?” He just sort of shrugged his shoulders and just said, well, no one’s really talking about it in the band, or anything like that. So I convinced him to start up a Bandcamp page for the group. I said, this Bandcamp thing is helping a lot of people, and you may want to consider putting up the catalog, at least so a new generation of people could hear it. He did, and I think it did well enough to fluff up the legacy to a certain degree.

Then, a couple of years later, we started discussing potential vinyl reissues. It wasn’t that I was trying to do the vinyl reissues myself. I was trying to think of other labels that could do it much better justice. I thought about Superior Viaduct or Drag City, or somebody like that that had the infrastructure in place that could do it justice. I reached out to a couple of people, and honestly, I got no pulse back, and whether these people were too busy – I doubt they were uninterested, but maybe that they weren’t thinking about it. I thought to myself, well, I know how to run a record label. I’ve got 3 or 4 cooking right now. I think I could do this. I just sort of took a gamble and said, fuck it. I’ll do it.

The initial focus was just to deal with the Thinking Fellers. In the course of the conversation I thought to myself, well, if we’re gonna go there, let’s see if we can’t deal with the extended family. Bring in all the characters. If the Thinking Fellers were the mothership, all the little babies could get scooped up to and try to get dealt with.

DH: You’re right, they really were the mothership, with many babies circling.

HM: Mark was like, well, you do whatever you want. This is your label and I’m happy to offer you all the Fellers material you need.

DH: I should probably know this, but what does the label’s name refer to?

HM: Oh, that was some nonsensical dada word play between me, Davies and Kearney. I was trying to come up with a name, and I’d reached out to those guys. We all have had this email thread for years where we email stupid shit to each other; dumb jokes and links, that sort of thing. And we all started riffing. Of course, Brandan emails me 75 nonsensical names, you know; “Pudding Lane” and this, that and the other, and Davies the same, and me the same. I just chose two words that seem to go together well, honestly, without any sort of focus about it. It was just like, Oh, here’s bulbous and monocle, and those two sound good together, and that was it. Zero intellectual depth to it whatsoever. Brandan made fun of me for a second; he goes. “That sounds really Wes Anderson”, and I almost barfed. Please dear Lord, don’t compare me to that.

DH: Tell me a little bit about your time in San Francisco. When did you move there, and, knowing how music-obsessed you were, where did you go and who did you see your first year or so there? What impressed you the most?

HM: My time in the Bay Area was in stages. I first moved out there in the late eighties, when I went to school at Cabrillo College in Aptos, just south of Santa Cruz. I went out to San Francisco in 1987 for the first time when I was 17 years old and growing up in Pensacola, FL. My parents let me go on a walkabout at that early age. I hit the road with my best friend at the time, and we drove cross-country and hit LA, and then drove up the coast, and ended up at San Francisco, the place with all this crazy music that I’d loved at that time, coming from hardcore and post-punk.

I dove head-deep into psychedelic music of the sixties at that age. I was into you name it; whatever late sixties psychedelia. San Francisco was mythical in my mind for being this sort of Eden of bohemian psychedelia, and I fell in love, of course. I mean just the whole of the West Coast, seeing that for the first time at that age really inspired me to just basically be like, I’m moving here next, the day after graduating high school, which is basically what I did. I packed everything up and moved out right after my senior year of high school and managed to land in Santa Cruz. A bunch of my friends were in San Jose. There were a bunch of us that all moved out together, so we had a small clique out there, we had all gone to high school together.

That was ‘88, ‘89, ‘90 and then I moved away. In 1990 I moved back to Florida for a couple of years, then came back out to San Francisco, for, like not even a year, then moved to Houston, Texas, in the early nineties, ‘92 to like ‘95; then also in that time period went back out to San Francisco for a few months, and then came back to Houston, and then came back to San Francisco full-time around 1995.

DH: I’m gonna assume that was work-related, or was that school-related?

HM: It was completely unhinged, no direction in my life, just trying to figure stuff out. And you know, friends here, friends there, I just finished college around that time, too, and I always knew I would be back in San Francisco, but there was kind of a period that I had to sort of put in time back where I’d grown up, before I could head back out fully-formed as a quote-unquote “adult” at age 24.

DH: So you’re really living there in fits and starts, right? There’s no sort of like one period where you landed, you stayed, and then you left 15 years later, or whatever.

HM: I did spend the latter half of the nineties there fully immersed. I lived in Noe Valley. I was two blocks away from Aquarius Records, before they moved down to the Mission. Then I ended up moving. I was living in Ingleside over there by City College for a few years as well.

DH: What was your musical experience there like? You said it was kind of you were looking for Eden, and something that was kind of like a holdover from the psychedelic sixties and the hippies. Did you find that when you were there, even in 1987? Or did you find something else entirely?

HM: it was a mishmash of stuff. Early on in my years in Santa Cruz, and even when I’d go back for those short visits, I was all over the place, man. We’d see music from whatever was available. I mean, the Santa Cruz years were definitely dominated by the Camper Van Beethoven world. You know, they were the locals. They were the bigwigs in town, so they would play a lot like at The Catalyst and other venues, and Monks of Doom, and The Ophelias, that sort of Camper universe ruled the roost, at least in Santa Cruz.

We would go up and see some shows at the I-Beam, but I was a young man, I wasn’t even 21, so there were a lot of clubs we couldn’t even get into. We had fake IDs at a certain point, to try to go see some of the bigger shows. A lot of times we wouldn’t be able to get in so we would see what we could see locally; there would be bigger festival stuff. And man, my memory. Honestly, I feel bad, but, like the details are….there were a lot of psychedelics involved at that time, and a lot of pretty heavy substance abuse.

DH: You’re definitely reminding me as well of the 21-and-over conundrum that I think San Francisco had a lot more issues with. I’m a couple of years older than you are. But in LA – I went to school down in Southern California – the clubs were 18 and over: Raji’s and the Anti-Club, which were the two main clubs there. You could hide your drinking surreptitiously. I guess by the time I actually made it to San Francisco I both had a fake ID, and/or I was already 21, so it wasn’t an issue.

HM: That limited the live experience a bit, and I literally had no money, so I wasn’t even collecting records. It was hand to mouth, and buying records was an insane luxury. I mean, we were barely surviving with just food and beer. That whole record collecting thing didn’t really start up again after high school until I’d moved to Houston.

By the time I got to San Francisco I was a full-bore record fiend, and it was a great time because that was the era when people were dumping tons of vinyl at every place that you know: Amoeba, Grooves, Flat Plastic Sound, Reckless. Rough Trade was even still around, I think.

DH: Yeah. They went South of Market for a while.

HM: That’s the one I remember, yep.

DH: What were some of your impressions, just either of the city itself, writ large, or the “state of the scene” when you were in San Francisco during those various years? With regard to underground rock music, what made the sound there interesting to you at the time, and did you feel that people were kind of recognizing it outside of town? I’d just love to get your takes on your sort of intermittent bursts within the city.

HM: Once I got back there, there was kind of this nostalgia revival in my mind of, “oh, I’m finally back, and I’m gonna like fucking never leave”. With regards to the scene itself, I mean, I wasn’t necessarily part of, or even deep friends with a lot of these folks. It would take at least three years for me to kind of start to meet a lot of these people, be it Gergis and his gang in the East Bay, and the Fellers, or whatever, and I mean, my contacts were all within the neighborhood where I lived in San Francisco. I was seeking out all the freaks that were into the Sun City Girls. That was a huge focal point for me, and from there was meeting one person after another, which introduced you to another. I wasn’t that connected, or a musician; I wasn’t on the inside at that point. I think a lot of people that were friends of mine now had probably left around that time, anyway, mid- to late nineties.

You were asking about some of the shows that had blown my mind back then. I remember seeing The Oblivians at the Kilowatt was a mind-blow for me. I think that was ‘95 or ‘96. Ghost, the Japanese band, came and played the same venue. Some of the bigger shows that would come through town at the Fillmore or the Great American. It was the Matador era, so Dirty Three or Sonic Youth, or you’d see a weird, odd show in Fruitvale (Oakland) with Caroliner playing some weird-ass loft. We’d get off the BART, and get egged out in fucking Fruitvale for just being on the street, and not being from the neighborhoods – it would all seem kind of dangerous.

The Fellers played a couple of shows out in Oakland; there was kind of a venue theater spot. A lot of stuff went down there; this would have been late nineties.

DH: In the early 90s they played the Heinz Club a few times in Oakland. It was kind of a short-lived, maybe a 2-years-at-best club, where a lot of really interesting bands would play.

HM: Yeah, that was Lexa’s joint, I guess, and I never got to see anything at the Heinz Club; I wasn’t around at that point. But a lot of all the friends that I know were; you know, Gergis and Pete.

DH: Oh, yeah, absolutely. Your “scene” was ever-present there, I think that that’s pretty much who was there.

HM: Right, right. And man, I mean speaking of – like I don’t know if you know Peter Conheim or not or know of him….

DH: Is it the same Peter from Oakland that worked at Saturn Records?

HM: Did he work on Saturn? I’m not sure. He was in Negativland recently. He was in Monopause, and I think also in Fibulator. He’s kind of the archivist, I mean – Peter was the guy that was filming and recording everything from that era. He’s the one with the massive audio and video archives from probably 1990 on up, and we’re gonna be utilizing a lot of this.

DH: What’s he doing with it? I was probably at some of those shows. What is he putting out – or is it already sitting on YouTube somewhere, or no?

HM: We’re not really sure. I mean, there’s stuff that’s been buried for years. He actually just bought the old Fantasy Studios.

DH: In Berkeley?

HM: Yeah. Him and a partner, and they’re revamping that. I mean, he’s been helping with a lot of tape restoration for these Fellers reissues. You know, baking tapes and doing a pre-master. And then Gergis has been remastering. So he’s being utilized in that sense, but he’s also gonna be helping, I think, in the future, cobbling together whatever disparate bands or one-offs that we would be able to make comps out of. He’ll be the best source for a lot of that stuff, he’s definitely got the archival goods.

DH: The Thinking Fellers material you’ve brought out to date has focused – except for the singles etc. comp – on 1993 material and afterward. At the time, I saw that year in particular as a somewhat clear dividing line for the band from what they’d been before: willing to write “pretty” songs; willing to clean up their sound in parts; but still willing to put utter absurdities on their records for no good reason. How did you see their evolution at the time?

HM: Well, the first thing I heard was Lovelyville. That was the first thing that I bought and I saw them on what I think was the Admonishing The Bishops tour, and I saw them again around the time of Strangers From The Universe. But that was in Houston, weirdly enough, right before I’d gone out to San Francisco. The reasons I chose what I chose to release first was from a logistical standpoint. You know, the idea to do this was to introduce the band to a new generation. I really wasn’t trying to bring a nostalgia trip back to anyone who had these records. The idea was there’s a whole generation of people that have never really listened to the Thinking Fellers, how would you best be able to introduce this?

I don’t really ever care about chronology or anything like that. I just went like, what are the most accessible releases that could at least, you know, crack this door open? I wasn’t gonna put out Mother of All Saints and be like, “hey, check out this band, they’re really cool and dense and weird and fucked up and indulgent”. From running a record label, you’ve got to think about these things. You know: what is the thing that’s gonna find the largest audience to at least introduce this? I’m going about it in a completely ad hoc way. The Funeral Pudding is gonna be in town on Tuesday, I’m gonna go pick up my copies. I’m gonna do Tangle after that. So we’re going all the way back to the beginning.

I think I’m gonna keep Lovelyville and Mother of All Saints as maybe the last two releases to do. That’s just how it’s gonna end up. There’s really no rhyme or reason, other than choosing Strangers and Admonishing seemed to make the most sense to me, from a financial standpoint honestly, and as a way to reintroduce or introduce the band to a new audience.

DH: Yeah, you’re bolstering the label so that you can do the Nuf Sed singles comp, right?

HM: Yeah, it’s gonna get weird. And the Whitefronts stuff which we should get to at some point. I’m not gonna put out a Whitefronts album, and then just lose a bunch of money and then be like, “Oh, this sucks! I’m out!”. I had to do enough loss leaders with Sublime Frequencies and several other labels that I’ve done over the last 20 years.

DH: It’s a good strategy, though. I mean you get to put out what you want, but you’ve sometimes got to think about actually bolstering the strength of the organization, right?

HM: Oh, yeah, I mean, it’s true but those are great records, too. I mean, Strangers From The Universe and so on.

DH: Absolutely. It was interesting. They actually got significant attention outside of town at that point. They really felt like a local band until then. In fact, I remember when Matador got excited about them and Gerard Cosloy came out, they played a Matador fest in San Francisco, probably around ‘91, and I was like, “Oh, my god! The rest of this country cares about the Thinking Fellers!”. “The rest” being Gerard and a few people in New York. But I was flattered, you know, like, our band, our band is going somewhere. Not that I had anything to do with it.

So how do you characterize Brandan Kearney’s Nuf Sed Records in the late 80s and through the 1990s? What made this a label worth paying attention to at the time, and how do you think that music will play now, should you put it out again?

HM: Nuf Sed was such a breath of fresh air for me just in regards to the humor, first and foremost. The complete lack of dogma and/or the inside joke-making was the way I understood it, and why I loved it, and I was drawn to it for reasons other than connections to the Sun City Girls and the Fellers. It was kind of a piss-take in the way it presented itself, definitely did not take itself seriously. Lots of humor there, be it ridiculous or dark.

In that sense, it aligned with my own ridiculous sense of humor as well, and taking the piss, which we did a lot of during that time, any sort of movement – I never really felt like I was part of any scene or whatever, and I never really was, because I always felt outside of it, sort of on the balcony, looking down, which is where I felt maybe the most comfortable, and not necessarily aligning myself to any one particular thing or another. I mean, even if I was buying a bunch of records that were coming out on the “in” labels at that time, I was still heavy into collecting, I don’t know, Folkways records, Arabic records, traditional Asian stuff. I was as much or more into that stuff.

I loved the energy of contemporary music and probably like you, Forced Exposure was my bible for sure. At that time, Byron and Jimmy were huge oracles for me, and a lot of the friends that I had also hipped me to some really cool stuff. That was such an intense 3 or 4 years; from ‘92 to ‘95 was such an avalanche for me, in regards to being introduced to whatever was current, but also, like, BYG, ESP, tons of obscure psychedelia. Also Sun Ra, I saw Pharoah Sanders back then. I was already heavy into free jazz. When you finally have disposable income, you’re just buying anything and everything that seems tangential to one or another of the releases. And then that classic era before the Internet, when you had to do a bunch of detective work, through reading liner notes or the credits and thank yous on the back. That was a real university education with regard to what was what.

DH: You’re also either working on or would like to work on a World of Pooh collection at some point. Are you able to say more about what that might have on it?

HM: I talked to Brandan. He nonchalantly shrugged his shoulders and was like, “Sure, whatever, If you think anybody will listen to it”. The World of Pooh comp is now in full throttle and almost done. Just a couple of weeks ago, I really dove back into what he had sent me. It’s basically all their material, even the original cassette, but I don’t think I’m gonna go quite that deep. I think it’s just gonna stick with the Barbara Manning years and tie up all the loose ends: the 7-inches, the comp tracks. Whatever wasn’t on The Land of Thirst.

DH: I made myself a CD-R of all that stuff probably 25 years ago. And that’s still one of my favorite CDs, with all the loose ends in one place.

HM: It’s hilarious, ‘cause I also just burned it to a CD-R, last week, and then I drove up to Seattle to do this Flea Market record fair, and listened to it all the way up and all the way down.

DH: I’d also love to know as much as you’re willing to share about The Whitefronts, and any involvement you might or might not have in bringing their music to a new generation.

HM: I have that album that they put out, Roast Belief. And I revisited that recently in a weird way. I was talking to someone I’ve seen in Seattle, this would have been a couple of years ago, but Martin Imbach is his name. He runs Georgetown Records. Martin was a big head back in the day in Seattle in the late eighties, or whatever, even mid-eighties, I think. He was talking about seeing them back in the day like, “Yeah, man, now, those guys were really fucking weird. They dressed up in Libyan robes, and were on acid”. And I kept thinking like, “Whoa! It sounds like Sun City Girls”, and he’s like, “they just were like total freaks, and it sounded like the Butthole Surfers”. So I pulled the record back out, and I just was like gobsmacked, because I hadn’t heard it in a long time, and finally, like, it made complete fucking sense to me, and I was just obsessed again, you know?

DH: And that’s what you’re thinking about bringing out again?

HM: No, no, so I’m in touch with one of the members, Skud. I think what we’re gonna do, and it’s pretty much set, is the unreleased second LP that was supposed to come out after Roast Belief. It’s as great as all their stuff. I’ve got a couple of the other cassettes too. Their stuff is just phenomenal. I mean, that’s a band to me that scratches every itch.

DH: I went to UC-Santa Barbara, and they were touted by my older cousin and his friends as the one local band that were, you know, “college kids” that were fantastic. Right when I got there in 1985, they were probably petering out and moving to San Francisco so I missed them entirely. But I did get to hear those cassettes; my cousin and I lived together and he would play them in our room. And I was like, this is crazy stuff.

HM: It’s incredible, man, it’s incredible stuff. It’s incredible. I’m really excited to bring that out, because, you know, as you said, mostly just the heads, the local heads. They have a lot of connections with some people that are still living. I don’t know if you know who Lindsey Thrasher is.

DH: Yeah, totally.

HM: Okay, well, you know, Phil Smoot, I think, was part of Vomit Launch for a minute. They dated back in the day. You know. Chas (Nielson, editor of Bananafish) knows them really well, too. Brandan is a huge fan. He has some of those cassettes. At the end of the day, beyond this unreleased album we’ll see what else we can do. But with those guys, they’re all in.

DH: I remember Roast Belief got written about, or just the Whitefronts got written about in Bananafish, and that too felt like huge validation because this local UCSB band all of a sudden is getting attention in this big fanzine. I was really excited for them. That’s the only Whitefronts coverage I ever saw anywhere, I think?

HM: Well, you know I did some detective work and pulled out some old FEs and Byron reviews them, and he was floored, too. He didn’t even really know how to go at it. But the end sentence was like, this is maybe one of the top picks of the issue or something. So we’ll see where that all goes, but for sure that’s gonna also happen, probably right after the World of Pooh release.

DH: Did you read Will York’s Who Cares Anyway book, and if so, what did you think about it – specifically the parts about the music you’re reissuing?

HM: I met Will 20+ plus years ago when he moved to San Francisco, I was touring with the Girls. This was the early 2000s, and we met because he did a big write up for the Bay Guardian at that time. He came out and had dinner with us, pre-show or whatever, and I knew that he was working on this book. I know he’s been at it for a long time, so finally, when it came out – it’s great. I love the book, especially the things that I care about; Flipper, and then the scene that we’re dealing with, be it Caroliner, Turkington, Brandan, and into the Feller zone, which is really the stuff that I most cared about. Some of the other stuff, I wasn’t ever really into. There was a lot of music in the Bay Area that also was for me personally a little cringy, that wasn’t my taste at all.

It’s well written. It’s an oral account from the horse’s mouth in a lot of ways, you know, which I really appreciated.

DH: That’s the best way to tell a story, I think.

HM: Yeah, agreed, and in that sense he succeeded really well, he let everybody kind of tell their own story. Some of it could be quote-unquote controversial. I think a lot of beefs were revealed, and that were only known about by scene insiders. I’m still curious if Grux has read the book or not.

DH: When did you leave San Francisco, and why?

HM: In 2000, I moved up to Seattle. I moved for whatever reasons you can imagine. The state of San Francisco was pretty intense. You know, the dotcom shit hit the fan. I was married at that time, and things got out of hand living wise. I’m sure they’re 10 times worse now. But all things being relative – at that point, the trajectory had gotten into the red of, like, unaffordability. We were lucky to get in when we did. I mean, our rent was nothing for years, and we had a big house with a yard, and it was a ridiculous amount of rent that we paid. The landlords were really cool, but we couldn’t leave that house because of that. So it felt like a kind of a ghetto prison. Any move would have tripled our expenses.

So I was like, fuck this, we’re out. My wife’s mom was moving up to the Puget Sound, up to Whidbey Island. We moved up to Seattle. At that point, I was already in touch and friends with Alan and a couple of other people up there, and so that made it a little easier to go up there and have friends already living there. That was an easy transition, and it was a glorious one. The ensuing years were quite magical.

DH: Is there a record you’d like to reissue or put out that you just know won’t or can’t happen for whatever reason?

HM: You know, honestly, and this sounds like a joke – I’ve mentioned this to Grux, who, you know, Grux is not the easiest person to to get a straight answer from – but I’d love to do a Caroliner’s Greatest Hits, and call it that. Caroliner Rainbow’s Greatest Hits, and cull from all the releases. I think people get so intimidated about where to enter. You know this complete maelstrom of prickly noise, but there are some really beautiful moments in there too, you know. Brandan was as much part of that band as anybody else. Gregg Turkington. You know that the Fellers were the band, for, like 3 albums, I don’t know if you knew that or not.

DH: Only from reading the Will York book, but I always thought it was like a collective of maybe 7 or 8 people. That kind of changed, but I didn’t realize it was so many people coming in.

HM: So many people. Phil Franklin, Laura Allen, all these guys were in. It was a revolving door, for sure. Alex Behr, etc.

DH: What else can we potentially expect from the label in the years to come?

HM: This might take a while, but the wheels are in motion. I’d love to do what I keep telling Chas, and I’ve kind of put him in charge. It’s kind of a Nuggets-style comp of, you know the super tendrils, or whatever – Archipelago Brewing Company, or Dumbhead, or San Francisco tentacles that that only existed for a minute or 3, or whatever stuff that only came out on cassette, or had only come out on an obscure comp here, there, just to kinda dig even deeper into that.

DH: There’s enough stuff on cassettes alone, some of which I’ve never heard. I know that Brandan put out that String of Pearls tape, and I’ve been asking him to digitize that for years, so I could actually hear it. I never owned that one.

HM: I’m kind of leaving it to Chaz and Peter and Gergis. There was an email thread going with a bunch of people about this. People like Geoff Soule. He lives here, too. I had a deluge of emails of – you can imagine everyone was like, “Oh, man, this would be great, this would be great”. And it’s kind of almost overwhelming for me.

DH: Triple album all of a sudden.

HM: Right. So I’m kind of leaving it to Chaz to sort of spearhead the thing to get it somewhat in a malleable fashion, and then I can kind of make the executive decision of what to include or not. So that could be one or two volumes of that kind of stuff.

You know, I’m not trying to be exhaustive. I mean, it’s such a subjective thing. It just has to be something that I think is worth reissuing, or turns me on musically, too. I’m not trying to be comprehensive or try to get it all reissued or heard for the first time. It really has a lot to do with finances and ability for me to give it the time. Sublime Frequencies is a full-time job. I’ve got other labels that come and go. That and having a fucking life.

It’s a hobby man, I mean, Bulbous Monocle was just such a whim to like, make it happen, because I’ve got the metaphorical production factory lined up. It’s easy for me to put this stuff together and get it run through a pressing plant. All that said, some other surprises may come down the pike.

Thanks so much to Hisham Mayet for his time, experiences and stories, and to Gail Butensky and Brandan Kearney for the photos…! Learn more about Bulbous Monocle here.